Siguza, 23. May 2025

tachy0n

The last 0day jailbreak.

0. Introduction

Hey.

Long time no see, huh?

People have speculated over the years that someone “bought my silence”, or asked me whether I had moved my blog posts to some other place, but no. Life just got in the way.

This is not the blog post with which I planned to return, but it’s the one for which all the research is said and done, so that’s what you’re getting. I have plenty more that I wanna do, but I’ll be happy if I can even manage to put out two a year.

Now, tachy0n. This is an old exploit, for iOS 13.0 through 13.5, released in unc0ver v5.0.0 on May 23rd, 2020, exactly 5 years ago today. It was a fairly standard kernel LPE for the time, but one thing that made it noteworthy is that it was dropped as an 0day, affecting the latest iOS version at the time, leading Apple to release a patch for just this bug a week later. This is something that used to be common a decade ago, but has become extremely rare - so rare, in fact, that is has never happened again after this.

Another thing that made it noteworthy is that, despite having been an 0day on iOS 13.5, it had actually been exploited before - by me and friends - but as a 1day at the time. And that is where this whole story starts.

In early 2020, Pwn20wnd (a jailbreak author, not to be confused with Pwn2Own, the event) contacted me, saying he had found an 0day reachable from the app sandbox, and was asking whether I’d be willing to write an exploit for it. At the time I had been working on checkra1n for a couple of months, so I figured going back to kernel research was a welcome change of scenery, and I agreed. But where did this bug come from? It was extremely unlikely that someone would’ve just sent him this bug for free, with no strings attached. And despite being a jailbreak author, he wasn’t doing security research himself, so it was equally unlikely that he would discover such a bug. And yet, he did.

The way he managed to beat a trillion dollar corporation was through the kind of simple but tedious and boring work that Apple sucks at: regression testing.

Because, you see: this has happened before. On iOS 12, SockPuppet was one of the big exploits used by jailbreaks. It was found and reported to Apple by Ned Williamson from Project Zero, patched by Apple in iOS 12.3, and subsequently unrestricted on the Project Zero bug tracker. But against all odds, it then resurfaced on iOS 12.4, as if it had never been patched. I can only speculate that this was because Apple likely forked XNU to a separate branch for that version and had failed to apply the patch there, but this made it evident that they had no regression tests for this kind of stuff. A gap that was both easy and potentially very rewarding to fill. And indeed, after implementing regression tests for just a few known 1days, Pwn got a hit.

So just for a moment, forget everything you know about kheap separation, forget all the task port mitigations, forget SSV and SPTM… and let’s look at some stuff from the good old times.

1. Lightspeed

First, a quick recap on this bug. This is the Lightspeed bug from Synacktiv (CVE-2020-9859 and possibly CVE-2018-4344). It’s in the lio_listio syscall, which lets you do asynchronous and/or batched file I/O. To keep track of all submitted I/O ops, the kernel allocates this struct:

struct aio_lio_context

{

int io_waiter;

int io_issued;

int io_completed;

};

The actual work is then performed on a separate thread, which is also responsible for freeing this struct once all I/O has been completed (in do_aio_completion):

/* Are we done with this lio context? */

if (lio_context->io_issued == lio_context->io_completed) {

lastLioCompleted = TRUE;

}

/*

* free the LIO context if the last lio completed and no thread is

* waiting

*/

if (lastLioCompleted && (waiter == 0)) {

free_lio_context(lio_context);

}

But in the case where nothing has been scheduled at all, that code path will never be hit, and so the current thread has to free this struct again, right from lio_listio:

case LIO_NOWAIT:

/* If no IOs were issued must free it (rdar://problem/45717887) */

if (lio_context->io_issued == 0) {

free_context = TRUE;

}

break;

if (free_context) {

free_lio_context(lio_context);

}

The problem is just that this check is racy. If work has been submitted to the other thread, but it has already completed by the time this check runs, then lio_context is a dangling pointer here. You can check the original blog post for more details, but in order to exploit this, we want the following sequence of events:

lio_listioallocateslio_context.- The work completes and

do_aio_completionfreeslio_context. - We reallocate the freed memory with something we control, such that

lio_context->io_issued == 0. lio_listioseeslio_context->io_issued == 0and frees our allocated object.- We reallocate it again with something else, and now have two entirely different allocations pointing to the same memory.

Now, we’re targeting 64-bit devices here, where the smallest zone is kalloc.16, which is where our lio_context goes. Two things help us massively here:

- Before iOS 14, allocations of all types shared the same allocation site, only bucketed by object size. So C++ objects, pointer arrays, user-provided data buffers - all in the same place and able to reallocate each other’s memory, giving us many targets to work with.

- Normally with a double free, it’s crucial to get a reallocation step in between the two frees, because otherwise you hit some unrecoverable disaster state. But in our case, once submitted,

lio_context->io_issuednever hits zero while allocated, and once it’s freed, the allocator on the OS versions we’re looking at will overwrite the first 8 bytes with a canary value XOR’ed with either the freelist pointer (zalloc) or the object’s address itself (zcache). Thus, the double free only happens if the object is reallocated in between the two frees, and has bytes 4 through 7 zeroed out! And while it can happen that something else on the system snatches the allocation away from under us and zeroes out the necessary bytes to trigger the double free, in practice this is very unlikely, so we’re able to retry this race many times until we get it right.

2. Spice

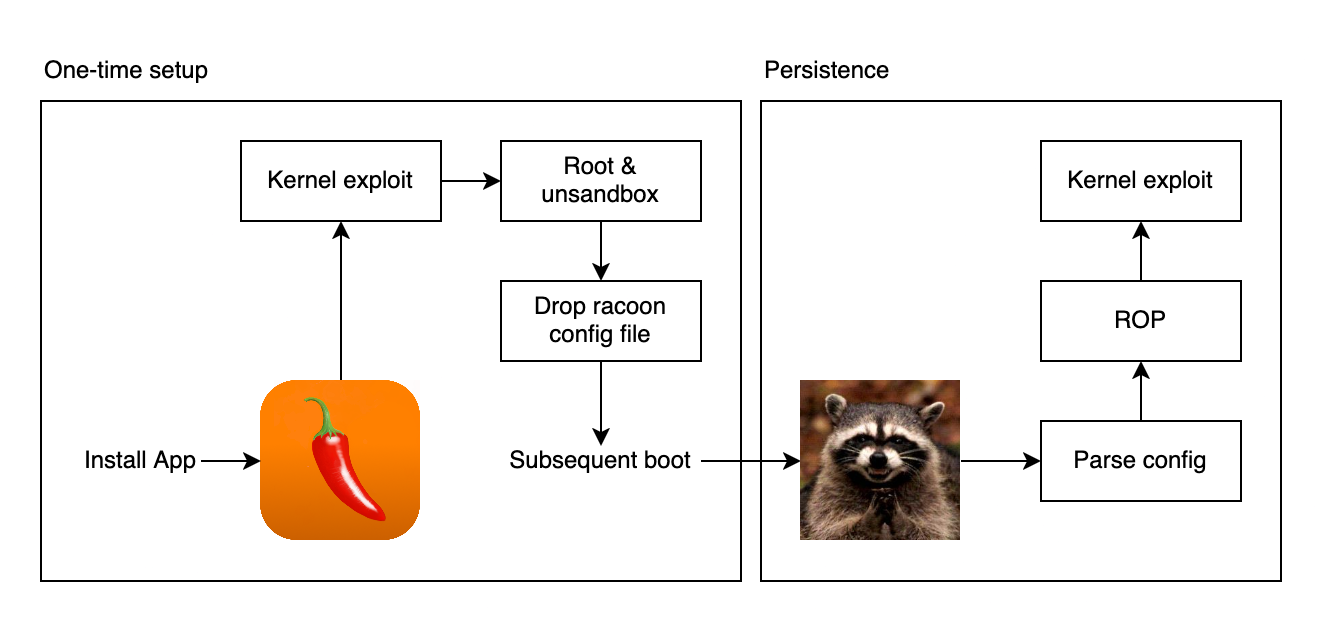

As mentioned, this bug had been exploited before, by a team that I was part of. That was in the Spice jailbreak/untether together with Sparkey and littlelailo, under our jailbreak team Jake Blair. This targeted iOS 11.x and was written at a time when iOS 13.x was latest, so some things were different than on 13.x and we had some 1days to work with, but a lot of concepts still apply. And while exploitation from racoon has already been documented in lailo’s 36C3 talk, that’s only half the story. Because originally, our planned installation flow was like this:

So we actually had two different variants of the kernel exploit: one for the app and one for racoon. Lailo’s talk details the one from racoon, but that has some important differences to the one from the app. Because while racoon runs as root, it has a much tighter sandbox than normal apps.

Our goal was the same in both cases: mach port forgery. If you were doing kernel exploitation before iOS 14, this was just the meta. Everyone and their mom was doing it, it’s been explained in detail many, many times so I’m not gonna rehash it here, but fact is: if you could get a user-supplied value interpreted as a pointer to a mach port, it was game over. And doing that was actually very straightforward with lightspeed:

- Trigger the first free of

lio_context. - Spray mach messages with an OOL mach ports descriptor of size 1 or 2 whose first entry is

MACH_PORT_NULL. This got placed inkalloc.16andMACH_PORT_NULLis0, so it setlio_context->io_issuedto0. - Trigger the second free of

lio_context(i.e. our OOL mach ports array). - Spray controlled data to

kalloc.16to replace the mach ports array with fake pointers.

The main difficulty here was just getting controlled data at a known address in the kernel, so that you had a fake pointer to spray. For A7 through A9(X) though, this was actually insultingly easy:

fakeport = (kport_t *)mmap(0, KDATA_SIZE, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANON, -1, 0);

mlock((void *)fakeport, KDATA_SIZE);

That’s it. There you go, that’s your “kernel” pointer. There’s no PAN, so you can just do userland dereference.

But alright, alright, we had A10 and A11 to take care of as well, so we began looking at some 1days.

We had a kernel stack infoleak due to uninitialised memory and a sandbox escape to backboardd, both by Ian Beer. Our plan had been to leverage those to either leak a pointer to shared memory we could write to, place data in the kernel’s __DATA segment, or something of that sort. But we never actually found a suitable target, and because of that the sandbox escape was left unfinished, so A10 and A11 were actually never supported from the app.

But the racoon side looks different, on a couple of fronts. First off, spraying controlled data is actually not as easy as it sounds. The common strategy for this was to hit OSUnserializeXML for rapid bulk unserialisation into virtually any chosen zone, and doing so via IOSurface::setValue, which additionally allowed replacing and removing individual properties at will later. But of course, racoon doesn’t have access to IOSurface, so we had to think of something else. Basically the only part of IOKit it has access to is RootDomainUserClient, and that just so happened to contain this bit in RootDomainUserClient::secureSleepSystemOptions:

unserializedOptions = OSDynamicCast(OSDictionary, OSUnserializeXML((const char *)inOptions, inOptionsSize, &unserializeErrorString));

The OSDynamicCast there just makes sure that the value returned by OSUnserializeXML is an OSDictionary, otherwise it substitutes it with NULL. In other words, if we unserialise anything that isn’t a dictionary at the top level - like, say, an OSData object - it will fail this check and the pointer to it will be lost, thus the object will be leaked. That’s obviously not great, but for spraying a couple dozen objects, it’s good enough. This is not a vulnerability per se, but it is a bug that Apple subsequently went and fixed.

Another thing that’s different in racoon is sysctls. Because unlike user apps, its sandbox profile allows blanket reading and writing of any sysctl. And unlike user apps, it runs as root, so it actually has the power to modify a whole bunch of sysctl values. And since most of those are globals that are stored in the kernel’s __DATA segment, once you know the kernel slide, putting data at a known address becomes trivial. In our case, we chose vm.swapfileprefix for this, which shouldn’t interfere with anything, at least while the exploit is running.

There’s just one problem: the kernel stack infoleak mentioned above has rather odd requirements. You need to hit an undefined instruction in one thread and then race the exception handler from another thread to reprotect the page to remove read permissions before it tries to copyin the faulting instruction. And then you need a third thread to receive the exception message and restart the first thread if the race failed. That just sounds like a massive pain, so we were looking for an easier option, and we found one: CVE-2018-4413 by panicall.

This was an infoleak in sysctl_procargsx that was patched in iOS 12.1, which allowed you to leak almost an entire page of uninitialised kernel memory from the kernel_map. So whatever objects you could spray and then free again, you could leak. That’s an easy win for both kernel code and heap pointers, and definitely enough to get the kernel slide. Thus, A7-A11 were all taken care of.

It would’ve almost also provided a way to pwn A10 and A11 from the app sandbox, if only the sandbox profile didn’t block sysctl_procargsx. But oh well.

All in all, there are much better kernel exploits for iOS 11 today, and the untether was the exciting part anyway.

3. unc0ver

Alright, now onto the real exploit. This time we’re talking A8 through A13, so just yolo’ing it with userland dereferences and ignoring A10+ was no longer an option. I had to work with just this double free.

But another thing I wanted to tackle was a regret that I had from multiple previous exploits I had written. During exploitation of memory corruption vulnerabilities, there will often be steps that can fail, such as freeing and reallocating some memory, which most of the time will put some object into a corrupted state. Usually that is not immediately fatal, but it will require explicit cleanup in order to preserve system stability, and it also requires going back to an earlier stage in the exploit and performing certain steps again.

In our case, this concerns multiple different kalloc.16 overlapping with each other. If we’ve got two OSData buffers pointing to the same backing memory and want to free one of them to reallocate it as an object of a different type but something else snatches it away from us, we can make this harmless by just not freeing the other OSData object yet that we still hold. But we’ll have to add it to our cleanup bucket and once we achieve kernel r/w, we’ll have to come back and set its size to zero so that the kernel won’t free the data buffer anymore when we destroy the object.

To account for this from the beginning, I designed the exploit with two layers. The lower layer starts multiple threads that call into lio_listio and a bunch more threads that unserialize OSData objects via IOSurface to race against it. The default number of threads is 4 freers and 16 racers, but these numbers can be adjusted. The data that is unserialized through IOSurface is an OSDictionary whose entries look like this:

*d++ = kOSSerializeSymbol | 4;

*d++ = sym(k);

*d++ = kOSSerializeData | 0x10;

*d++ = 0x41414141; // io_waiter, ignored

*d++ = 0; // io_issued, must be 0

*d++ = 0x69696969; // io_completed, ignored

*d++ = k; // padding

(If you’re unfamiliar with this, this is just the OSSerializeBinary format. See OSUnserializeBinary in XNU. And sym() is just a function I wrote to transpose an arbitrary uint32_t into one without any null bytes.)

More about this in a minute. Since each unserialisation call will create many such objects and since we just spam this call from multiple threads, it is highly likely that we’ll end up with the following scenario:

lio_contextis freed.- Its memory is reallocated as

OSDatabuffer. lio_context/OSDatabuffer is freed again, creating UaF.- Its memory is reallocated again as buffer for another

OSDataobject.

Thus we’ll end up with two OSData objects pointing to the same data buffer. This is where the magic values 0x41414141 and 0x69696969 come into play. After our racing, we go through all OSData values in our IOSurface and look at their contents. If any of them don’t have our magic values, then they must have been stolen from us by something else on the system. We’ll mark these for later cleanup and will ignore them for now. Otherwise we’ll move on to the value k at the end of the buffer. This value is linked to the key that the OSData has in the dictionary, which is crucial for letting us figure out whether an overlap occurred. If we look up an object for sym(123) and the value in the buffer at offset 0xc is not 123, then we know that this data buffer has been reallocated for another OSData object - and moreover, we know which OSData object, since it contains the value k that lets us look it up on the IOSurface. We can thus create a mapping of overlapping objects via their keys in the dictionary.

This is what the maybe_reyoink/overlap functions in the code do. They create a structure to hold this information and return it to the upper layer, and they can be called into at any time to acquire more overlapping OSData objects if needed.

So the upper layer gets supplied with overlapping OSData objects, and it can use this later to construct a fake mach port by freeing one of the OSData objects, spraying some mach messages with OOL port descriptors, then freeing the other OSData object, and then reallocating it with a new OSData object that contains a pointer to a fake task port. That part is easy, but once again we’re left with the problem of needing to leak a kernel address at which we can put controlled data. But with the aforementioned steps, we can actually leak some heap addresses already. All we have to do is read the OSData contents after the first reallocation as OOL ports descriptor array, and we get the raw kernel pointers of whatever mach ports we send in the OOL descriptor. We’re gonna use that later to leak the addresses of our task port and our service port to IOSurfaceRoot to make the rest of the exploit easier, but that’s beyond the scope of this write-up. Now, we could spray a lot of mach ports, leak their addresses until we have a full page that we hold all references to, free them all, and then try and trigger a zone garbage collection to get the memory into a different zone, but that is slow, expensive and annoying to get right. The same problem applies to OSContainer objects, and pretty much all other pointer arrays you can think of that you could get into kalloc.16. It would be so much easier if we could just get the address of a buffer whose contents we control into kalloc.16… something like shared memory, or so. But such things are rare.

After looking through XNU sources for a couple of days though, I did find a possible candidate: IOMemoryDescriptor. It has a field called _ranges, which is an array of IOVirtualRange, which is literally just:

typedef struct{

IOVirtualAddress address;

IOByteCount length;

} IOVirtualRange;

A single one of those fits perfectly into kalloc.16. There’s just one catch: if there is only a single range, then IOMemoryDescriptor points the _ranges field at another field _singleRange instead and saves on doing a heap allocation. There is no way to reach that code path in IOMemoryDescriptor with just one range. However, a subclass of IOMemoryDescriptor, IOBufferMemoryDescriptor, does exactly that, explicitly:

_ranges.v64 = IONew(IOAddressRange, 1);

_ranges.v64->address = (mach_vm_address_t) _buffer;

_ranges.v64->length = _capacity;

Now all we need is a place in the kernel where we can allocate an IOBufferMemoryDescriptor at will and also get it mapped into our address space. One convenient place for this is the AGX interface, aka. IOAcceleratorFamily2 (note that this has since been refactored into IOGPUFamily in iOS 14, so the details here only apply to 13.x and older).

If we open a userclient of type 0 on IOGraphicsAccelerator2, it will give us an IOAccelContext2, which lets us map three different memory descriptors via ::clientMemoryForType(). I don’t know what any of them are actually for, but types 1 and 2 have a default size of 0x4000 bytes, while type 0 has a size of 0x8000 bytes. Since we’d like to be able to uniquely identify the victim descriptor, the 0x8000 one is the one to go with here. (And we’re gonna need two pages of memory anyway for later stages of the exploit, so that’s convenient.) Before we can map it, however, we first need to initialise our userclient some more. We do that by opening another userclient on IOGraphicsAccelerator2 (type 2, IOAccelSharedUserClient2) and passing it to the first userclient via ::connectClient(). This will actually allocate our IOBufferMemoryDescriptor already, so we do the following in a loop:

- Open an

IOAccelContext2. - Grab the next two overlapping

OSDataobjects. - Free one

OSDataobject. - Call

IOConnectAddClient()on ourIOAccelContext2with anIOAccelSharedUserClient2that we opened earlier, outside of the loop. - Read back the other

OSDataobject and check if the first 8 bytes are a plausible page-aligned kernel pointer and the second 8 bytes are0x8000. - If we found that, break out of the loop, otherwise close the

IOAccelContext2and continue with the loop.

Now we can map the memory descriptor into our process and know its kernel address, but we’ve actually still got one problem: the memory is created as pageable (with kIOMemoryPageable), and since we’re gonna be forging a mach port and a task object here, these data structures may end up in situations where preemption is disabled, so we really want to fault those pages in on the kernel side. Once again, I don’t know what the code in question is actually supposed to do, but I figured out that I could trigger this by calling into IOAccelContext2::processSidebandBuffer, which is called indirectly from IOAccelContext2::submit_data_buffers, which is external method 2. So just call this twice with the right data structures prepared on shared memory. ::processSidebandBuffer() reads this structure from 0x10 bytes off the start of shared memory:

struct

{

uint16_t tok;

uint16_t len;

uint32_t val;

}

The first is some magic, the second is the length divided by 4, and val is some value whose significance I don’t know. All we care about is that the first structure we place on shared memory is valid (tok == 0x100 works) and spans an entire page, so that ::processSidebandBuffer() advances to the second page and faults it in. After that, it can error out, so on the second page we can put whatever. And with that, we now have controlled data at a known kernel address, which we can directly read and write to.

Now all that’s left to do is construct a fake task, fake port, pull a UaF and switcheroo on a mach ports OOL descriptor, construct an arbitrary read primitive, yada yada. All been done a hundred times.

Perhaps the only noteworthy thing at this point is the bypassing of zone_require, but even that should be well-known to anyone who was around during the iOS 13 days. zone_require was just completely broken by the fact that it allowed pages from outside the zone_map, where it would simply take the first 0x20 bytes of the page as page metadata, so all you had to do was populate that with the right zone index, and you had just minted yourself a pass for any zone of your choosing. This is also why we need two pages: one for tasks and one for mach ports.

This tiny bit of info was actually the only reason I had to not publish the exploit right away. But alas, it is public on GitHub now at last.

4. Aftermath

The scene obviously took note of a full 0day exploit dropping for the latest signed version. Brandon Azad, who worked for Project Zero at the time, went full throttle, figured out the vulnerability within four hours and informed Apple of his findings. Six days after the exploit dropped, Synacktiv published a new blog post where they noted how the original fix in iOS 12 introduced a memory leak, and speculated that it was an attempt to fix this memory leak that brought back the original bug (which I think is quite likely). 9 days after the exploit dropped, Apple released a patch, and I got some private messages from people telling me that this time they’d made sure that the bug would stay dead. They even added a regression test for it to XNU. And finally, 54 days after the exploit dropped, a reverse-engineered version dubbed “tardy0n” was shipped in the Odyssey jailbreak, also targeting iOS 13.0 through 13.5. But by then, the novelty of it had already worn off, WWDC 2020 had already taken place, and the world had shifted its attention to iOS 14 and the changes ahead.

And oh boy did things change. iOS 14 represented a strategy shift from Apple. Until then, they had been playing whack-a-mole with first-order primitives, but not much beyond. The kernel_task restriction and zone_require were feeble attempts at stopping an attacker when it was already way too late. Had a heap overflow? Over-release on a C++ object? Type confusion? Pretty much no matter the initial primitive, the next target was always mach ports, and from there you could just grab a dozen public exploits on the net and plug their second half into your code.

iOS 14 changed this once and for all. And that is obviously something that had been in the works for some time, unrelated to unc0ver or tachy0n. And it was likely happening due to a change in corporate policy, not technical understanding.

Perhaps the single biggest change was to the allocators, kalloc and zalloc. Many decades ago, CPU vendors started shipping a feature called “Data Execution Prevention” because people understood that separating data and code has security benefits. Apple did the same here, but with data and pointers instead. They butchered up the zone map and split it into multiple ranges, dubbed “kheaps”. The exact amount and purpose of the different kheaps has changed over time, but one crucial point is that user-controlled data would go into one heap, kernel objects into another. For kernel objects, they also implemented “sequestering”, which means that once a given page of the virtual address range is allocated to a given zone, it will never be used for anything else again until the system reboots. The physical memory can be released and detached if all objects on the page are freed, but the virtual memory range will not be reused for different objects, effectively killing kernel object type confusions. Add in some random guard pages, some per-boot randomness in where different zones will start allocating, and it’s effectively no longer possible to do cross-zone attacks with any reliability. Of course this wasn’t perfect from the start, and some user-controlled data still made it into the kernel object heap and vice versa, but this has been refined and hardened over time, to the point where clang now has some __builtin_xnu_* features to carry over some compile-time type information to runtime to help with better isolation between different data types.

But the allocator wasn’t the only thing that changed, it was the approach to security as a whole. Apple no longer just patches bugs, they patch strategies now. You were spraying kmsg structs as a memory corruption target as part of your exploit? Well, those are signed now, so that any tampering with them will panic the kernel. You were using pipe buffers to build a stable kernel r/w interface? Too bad, those pointers are PAC’ed now. Virtually any time you used an unrelated object as a victim, Apple would go and harden that object type. This obviously made developing exploits much more challenging, to the point where exploitation strategies were soon more valuable than the initial memory corruption 0days.

But another aspect of this is that, with only very few exceptions, it basically stopped information sharing dead in its tracks. Before iOS 14 dropped, the public knowledge about iOS security research was almost on par with what people knew privately. And there wasn’t much to add. Hobbyist hackers had to pick exotic targets like KTRR or SecureROM in order to see something new and get a challenge. Those days are evidently long gone, with the iOS 19 beta being mere weeks away and there being no public kernel exploit for iOS 18 or 17 whatsoever, all while Apple’s security notes still list vulnerabilities that were exploited in the wild every now and then. Private research was able to keep up. Public information has been left behind.

5. Conclusion

It’s insane to think that this was a mere 5 years ago. I think this really serves as an illustration to just how unfathomably fast this field moves. I can’t possibly imagine where we’ll be in 5 years from now.

Finally, I’d like to thank Pwn20wnd for sharing this 0day with me and choosing to drop it as part of a public jailbreak. That was a very cool move. I’d also like to thank whoever unpatched the bug in iOS 13.0. That was a very cool move too. And I’d like to thank everyone that I’ve learned from before these changes hit, and everyone that I’ve worked with afterwards. It wouldn’t have been possible for me to keep doing this alone.

If you have questions, comments, typos, or anything else, I’m just gonna link my website now. Whatever the most up-to-date way to contact me is, it will be linked there.